The fix was in against black Louisianians when 134 delegates gathered at Tulane Hall in New Orleans in February 1898 to draft a new state constitution.

Their marching orders: whitewash the voter rolls as thoroughly as possible — without running afoul of federal law.

Those rolls had swelled with black voters during Reconstruction. Their numbers had reached 130,000 in Louisiana, rivaling white voters in a state in which about half the population was black.

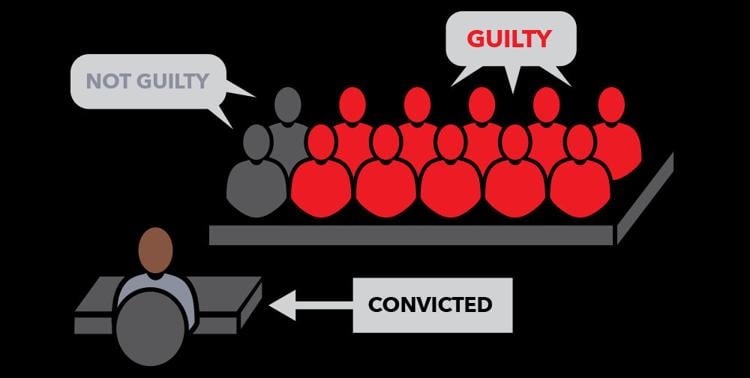

For the last 120 years, Louisiana has had an unusual and long-standing allowance for split jury verdicts in felony cases.

E.B. Kruttschnitt, a lawyer and New Orleans school board president who led the 1898 convention, bluntly described the gathering’s purpose.

Voters “have intrusted to the Democratic party of this State the solution of the question of the purification of the electorate. They expect that question to be solved, and to be solved quickly,” he announced.

The goal was to eliminate "the mass of corrupt and illiterate voters who have during the last quarter of a century degraded our politics," he said.

Many of the laws of the 1898 convention have been erased over time, chiefly by court rulings and federal legislation during the civil rights era.

Can't see timeline below? Click here.

But one product of that ugly meeting remains largely intact: a constitutional provision that abandoned Louisiana’s long-standing practice of requiring unanimous jury verdicts to send people to jail. After the convention, only nine of 12 votes would be needed, a practice unique in America.

The measure was one of several designed to speed things along in parish courtrooms and, in Kruttschnitt’s words, “relieve the parishes of the enormous burden of costs in criminal trials.”

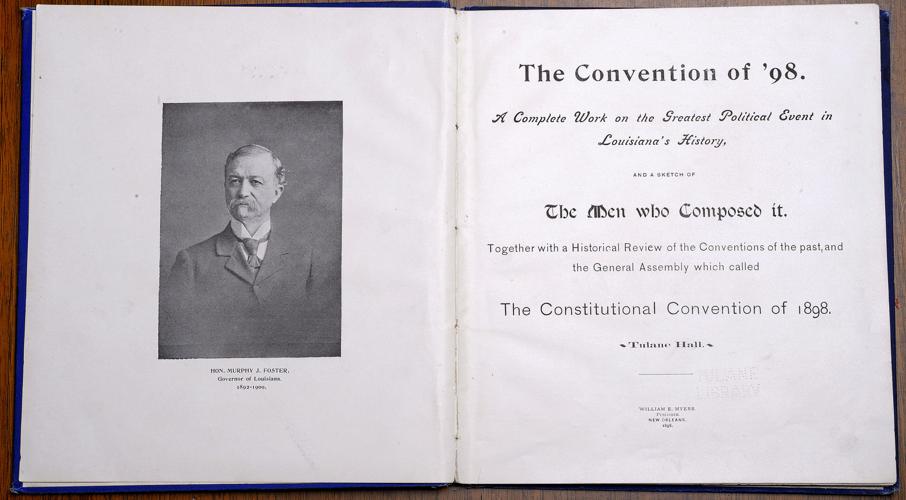

This photograph is seen in a book titled ÒThe Convention of Õ98: A Complete Work on the Greatest Political Event in LouisianaÕs History and a Sketch of The Men Who Composed ItÓ found in the library of the Louisiana Research Collection at Tulane University in New Orleans, La., Tuesday, March 27, 2018.

But efficiency wasn’t the only goal. As the curtain rose on the convention, the Comité des Citoyens, a mostly black and Creole civil rights group based in New Orleans, was taking aim at so-called "Jim Crow juries" — those that excluded black people.

The group already had become known for championing the cause of Homer Plessy, who challenged the segregation of rail cars in Louisiana. The case of Plessy v. Ferguson, decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896, legalized the “separate but equal” doctrine in the country for the next six decades.

Constrained by rulings

Although the Plessy ruling was a victory for white supremacists, the delegates to the 1898 convention knew they couldn’t simply ban black jurors, even if that was their aim.

Congress in 1875 had made it illegal to exclude people from jury service "on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude." And in 1880, the Supreme Court for the first time reversed a state conviction because of the exclusion of black jurors when it deemed West Virginia's blanket ban on them to be unconstitutional.

Less than a year before the Louisiana delegates met, a Creole man had been mistakenly seated on a federal jury in New Orleans and then booted off, provoking a fierce response led by New Orleans civil rights attorney Louis Martinet — and just as strident a retort.

On the eve of the 1898 convention, a U.S. senator from New Hampshire — prodded by Martinet — was demanding that the U.S. attorney general account for black participation on state juries.

Can't see video below? Click here.

The Daily Advocate quipped that the Northern senator ought to retire to “a clime hotter than this,” in a broadside launched a week before the convention.

“It is unfortunately too true that many negroes serve on juries in this State and the interests of justice are not subserved thereby,” the editorial said.

“Even intelligent negroes in this State prefer to be tried by white juries,” it went on, because “in the majority of instances the negro juryman is governed by his feelings rather than by the law and the evidence.”

Convention delegates were more circumspect as they ratified several changes to jury rules they said were designed to save money and speed the route to trial and conviction.

Misdemeanors now would be tried before judges, not juries. Lesser offenses would be tried by juries of just five members. And in the state’s guiding document, which went into law without a public vote, the delegates approved 9-3 verdicts for serious felonies.

The court minutes from the February 2013 trial of Jarrell Arline on a charge of dealing cocaine are so cursory they border on cryptic.

Tulane University history professor emeritus Lawrence Powell said the strength of the Afro-Creole movement in and around New Orleans may be why Louisiana, and no other Deep South state, took such a dramatic turn away from centuries of Anglo-Saxon tradition.

But there is no mention of the divided-verdict rule in the convention’s official journal, and Powell argued that the delegates were careful to leave little record of their real intentions.

“They were very cryptic, and it was almost self-consciously racially neutral. They had to use stratagems and ruses,” he said.

Still, Thomas Semmes, a former Confederate senator who headed the convention’s judiciary committee, crowed that the delegates had fulfilled their mission “to establish the supremacy of the white race in this State to the extent to which it could be legally and constitutionally done.”

Can't see video below? Click here.

The new constitution

The split-jury law would remain intact, despite countless subsequent revisions to the state constitution, until 1973, when lawmakers altered it after a divided U.S. Supreme Court had validated less-than-unanimous verdicts in state courts but forbade them in federal ones.

Ten jurors have since been required for a verdict in serious felony cases in Louisiana, though juries in capital trials must still reach unanimity.

The 1973 constitutional convention was a remarkable moment in Louisiana history: Just a few years after civil rights struggles roiled the South, a biracial group of 132 delegates rewrote the entire Louisiana constitution, simplifying it from some 700 pages to a slim 47. Voters ratified the new constitution in 1974 with 58 percent support.

Among the delegates, 11 were black and 11 were women, according to the convention’s chairman, E.L. “Bubba” Henry.

“It started off a little bit contentious because we didn’t know one another,” Henry said recently. “The longer we worked together, we started liking each other.”

Though a transcript shows he participated in the debate over jury verdicts on Sept. 8, 1973, Henry said he couldn’t recall it.

But the racial origins of the split-jury law never came up that day.

The law’s defenders argued a change wasn’t necessary. After all, the Supreme Court had approved Louisiana's system just a year earlier. Why risk an increase in hung juries?

Chris Roy, an Alexandria attorney and vice chairman of the convention, ripped the 9-3 verdict rule in effect at the time — noting that it allowed for a conviction even when one-fourth of a jury believed the defendant innocent.

"My point ... is that if the rest of the United States can require unanimous verdicts and the federal system can require unanimous verdicts, why can't we in Louisiana require at least five-sixths verdicts to convict?" he asked his fellow delegates.

Roy proposed a change: require unanimity in all cases where a conviction mandated a sentence with no parole. Armed robbery, with its 99-year maximum sentence, was his case in point.

For all other major felonies, Roy proposed raising the required majority for a verdict to 10 votes.

In pushing for the change, Roy told the delegates it was “generally ugly, poor, illiterate and mostly minority groups” members that get convicted by juries.

“It wasn’t a black-white issue, although it was likely to be something that played a part in the decision,” Roy, now 82, said in a recent interview.

His proposal met with resistance led by I. Jackson Burson Jr., at the time a St. Landry Parish prosecutor who scorned Roy’s view that 9-3 verdicts didn’t pass the sniff test for "beyond a reasonable doubt."

“Didn’t the U.S. Supreme Court uphold this as constitutional?” Burson asked.

Walter Lanier Jr., a Lafourche Parish attorney who would go on to become a judge, crafted a compromise: unanimous verdicts in capital cases, 10-2 verdicts needed in cases "in which the punishment is necessarily confinement at hard labor."

He maintained the split-verdict system was a laudable “modernization” of criminal justice, a field in which he described Louisiana as a national leader.

In a recent interview, Lanier, 79, said he suspected the split-verdict principle got here in the first place by way of the state’s legal roots in the Napoleonic code — a false assumption. He’d been unaware, he said, of its genesis in the racist convention of 1898.

“I don’t remember anything about that. I remember just talking about what was on the books,” Lanier said.

At the time, his attitude was, “Let’s get something reasonable that we could operate with. Nine out of 12, 10 out of 12 — big deal,” he said.

“Most of the juries I’ve seen have been unanimous. I wasn’t even thinking in those (racial) terms, or even paying attention to those terms.”

Burson, now 79, said recently that he actually favored a change as well, but feared Roy’s push for unanimity would draw “opposition we didn’t want” to the new constitution as a whole.

“I knew enough about the genesis of most of the laws passed in the earlier constitution,” Burson said, but “I felt like if we came and hit people by moving from nine to unanimous, we were going to have a difficult time. I’d rather make progress than aim for the moon and get nothing.”

The modified rule passed with scant opposition — a 99-5 vote in favor of Lanier’s compromise. It included one other change: Instead of five-member juries that needed to be unanimous for lesser felonies, the delegates agreed that those juries would have six members and could convict or acquit on the agreement of five.

The right of a defendant to be judged by “a jury of one’s peers” is a bedrock concept in American justice, dating to ancient English common law.

It was seen as a neat parallel to the five-sixths requirement the delegates approved for 12-member juries. But the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t see it that way, striking down 5-1 criminal verdicts six years later.

Since then, those “six-pack” or “bobtail” juries have been required to return unanimous verdicts.

‘Nothing revolutionary’

Thomas Velazquez, of New Orleans, the only known surviving black delegate to the convention, told The Advocate he didn’t recall the debate over the verdicts issue. He held a degree in chemistry and sat on the committee for the environment.

Understanding Louisiana's non-unanimous jury law findings: Interactive, animated slideshow

(Click image below)

But Velazquez, 78, said he does recall a racial dynamic to the proceedings.

“You got to remember, it’s almost a light year from 1973 to today. Anything you think about, there was a flavor of it there,” he said.

“Every effort was made to kind of iron it out,” he added. But “it would seem an advancement in the struggle could have been greater. People were there to protect certain things. I think a great step forward was made in many ways, but you got to realize, Louisiana is a conservative state. There was nothing revolutionary going to take place at the convention.”

Edwin Edwards, who convened the 1973 convention in the first of his four terms as governor, initially defended the split-verdict compromise in an interview with The Advocate last summer.

“I like the rules. At some point, you’ve got to decide where the line of demarcation is,” said Edwards, now 90.

“Now, there are some people who think that in all trials, there should be a 12-person jury and a unanimous verdict. But that would burden the legal system a great deal and add greatly to the expense of people who are charged with crimes.”

Edwards then went on to complain bitterly about his 1999 federal trial, in which he was convicted 11-0 on charges of extorting nearly $3 million from casino license applicants. He served eight years and was released in 2011.

The unusual outcome came after U.S. District Judge Frank Polozola, in Baton Rouge, removed a juror — thought to be pro-Edwards — after deliberations had begun. Federal trials require unanimous jury verdicts.

“It’s the only time in federal jurisprudence in Louisiana that 11 people on a jury convicted someone of a federal crime,” Edwards said, boasting ruefully.

After reflecting on his own case, Edwards told The Advocate that perhaps it is time to require unanimous verdicts in state trials in Louisiana as well as federal ones — at least when a lengthy prison sentence is in the offing.

“I would require it in any case as serious as the one I was facing,” he said. “There’s a saying in Louisiana that you’ll never find 12 people on a jury to convict Edwin Edwards. And in four trials, they didn’t do it.”

‘They covered their bases’

Following the changes in 1973, defenders of today’s split-verdict system in Louisiana view its racist history as a mere historical footnote.

But to Calvin Duncan, the rule’s inception in the late 19th century was the original sin. "The racial intent of it never went away. That's still there,” Duncan said. “The intent was to make sure African-American votes are not counted."

Duncan, 54, learned about the state's unusual jury system from behind prison walls, during more than two decades as an inmate lawyer at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

His own conviction, for the 1986 murder of David Yaeger in New Orleans, came in a capital trial in which the jury rejected a death sentence.

Decades later, the Louisiana Supreme Court ordered a new hearing for Duncan based on an apparently false statement made by law enforcement. Prosecutors then agreed to let him plead guilty to manslaughter and armed robbery in 2011 in exchange for his immediate freedom.

While in prison, Duncan knew nothing about the genesis of Louisiana’s split-jury law as he sought avenues to attack the convictions or sentences of his fellow prisoners.

"I just knew the Supreme Court said it was OK," Duncan said. “I never tried to rationalize why. The reasons that came behind it, that way of thinking, didn't come until years later."

What he would learn, once freed, spurred Duncan on a mission to abolish a century-old staple of Louisiana justice.

From an office in New Orleans, Duncan scours state court rulings, mails appeal packages to inmates and works with Ben Cohen, an attorney with the Promise of Justice Initiative, to file petition after quixotic petition to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Duncan counts 21 such petitions filed since 2013, each one arguing that the nonunanimous jury rule, born in white supremacy, retains its racist stench.

To Duncan, it’s black and white.

The court minutes from the February 2013 trial of Jarrell Arline on a charge of dealing cocaine are so cursory they border on cryptic.

“The odds of getting a black person on a jury back then was hard. Getting one was hard. If a miracle happened, you get two,” he said. “So they covered their bases.”

But the high court so far has declined to revisit the 1972 ruling that critics describe as a constitutional hangnail — an anomaly of Sixth Amendment jurisprudence.

The U.S. Constitution does not say how large juries should be or what vote is needed for conviction. The Sixth Amendment says only that "the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed."

The 'one exception'

The Supreme Court’s decision came in a pair of challenges from Oregon and Louisiana, the only states to allow split verdicts in felony trials.

Eight justices agreed that the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of a right to a jury trial applies to federal and state courts equally. They fell into two camps: Four justices said juries must be unanimous at both levels, and four others said unanimity was optional at either level.

Justice Lewis Powell broke the tie, casting jury unanimity as an indispensable feature of America's federal trial system “on the basis of history and precedent” but declaring it optional for states.

By then, the court already had ruled that juries with fewer than 12 members were allowed, at least in lesser cases. The tradition of 12 people on a jury was "a historically accidental figure ... wholly without significance 'except to the mystics,' ” Justice Byron White wrote.

Neither the size of the jury nor its unanimity is fundamental to the jury trial’s purpose of protecting defendants from overly zealous prosecutors or judges, White concluded. Rather, community participation and the freely applied "common sense judgment of a group of laymen" are what do it.

The Supreme Court has since recognized the peculiarity of that 1972 decision, describing it in 2010 as the “one exception” to a general rule that rights guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution apply equally to states and the federal government.

But for nearly 46 years, the high court has refused to tamper with it, even as it ruled in 1979 that Louisiana’s allowance for dissent on six-member juries — in other words, 5-1 verdicts — was unconstitutional.

And the Louisiana Supreme Court has repeatedly followed suit.

Someday, Duncan insists, he'll prevail.

"I (keep filing challenges to split verdicts) because the law is wrong, and someday, some judge is going to have the courage to say it's wrong," he said.

“The government has the burden of proof: You relieve them of that burden. The government’s obligation ain’t to convince 10 people; it’s to convince the jury that a person is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.”

A signal of change?

Duncan said he sees a glint of hope in a recent request by the U.S. Supreme Court for Louisiana to spell out its opposition to a legal challenge to the law — the first such request in eight years.

It came in a petition filed last year on behalf of David Wayne Sims, who was convicted in 2015 of aggravated rape in Calcasieu Parish on a 10-2 vote and was sentenced to mandatory life in prison. The same jury unanimously found him guilty of sexual battery as well.

Critics of split verdicts in state courts have argued that the framers of the Constitution didn’t enshrine unanimity in the Sixth Amendment because it went without saying. Such a requirement had been passed down from the Middle Ages, they say: Jury verdicts and unanimity were synonymous.

But in the state’s response, filed March 23, Attorney General Jeff Landry’s office argued that unanimity isn’t mentioned in the Constitution because it didn’t make the cut.

James Madison, the "father of the Constitution" who would become the country’s fourth president, had proposed an explicit requirement for unanimity. It was “considered and rejected” by the Senate, Landry’s office wrote.

Landry’s office also argued that the 1898 Louisiana Constitution is “long defunct,” and that the “suggestion that Louisiana’s rule ‘disenfranchises African-American jurors’ is unfounded.”

At the top of the state’s case against changing Louisiana’s law is the legal principle of “stare decisis,” the idea that courts generally shouldn’t mess with laws that repeatedly have been upheld.

Dumping the law now would “bring great instability and unpredictability to Louisiana and Oregon,” Louisiana Assistant Attorney General Colin Clarke wrote — particularly if the court were to make such a change retroactive and open the floodgates to legal challenges of decades-old convictions.

Southern University law professor Angela Allen-Bell, who has written extensively against Louisiana's non-unanimous verdict law, photographed Friday, April 6, 2018 in her office.

Angela Allen-Bell, a Southern University law professor and critic of the split-verdict rule, argues that mounting research on its racist origins — along with The Advocate’s research on its effects today — puts the lie to any justification for the law to remain.

She said the 1973 convention didn’t “sanitize” the law simply because the delegates debated it in nonracial terms.

“There has been no moment in the state of Louisiana that we have sat down and been honest about why this got started,” she said. “At no point did Louisiana voters get a memo saying, 'We did this for racist reasons.' ”