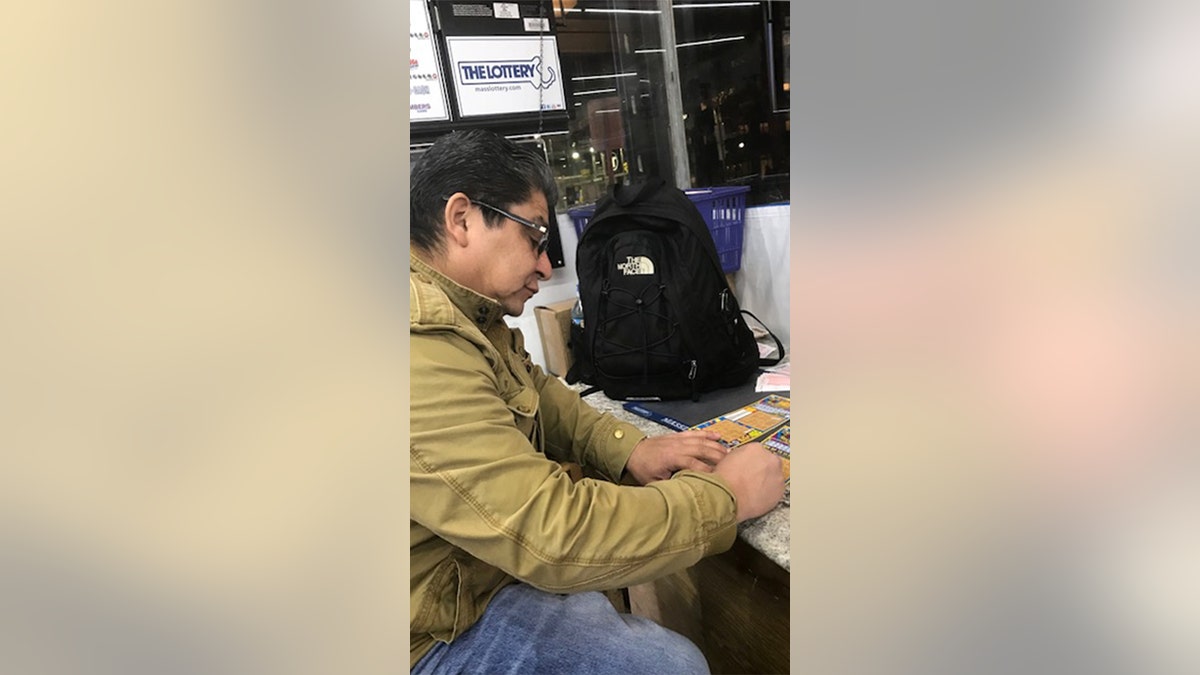

East Boston resident David Aguirre has on some days bought $100 worth of lottery tickets. (Elizabeth Llorente)

EAST BOSTON, Mass. – Along a stretch of the Maverick Square neighborhood, dotted by bodegas and mom-and-pop eateries, they wrap up their long days of work, and make the familiar pilgrimage to the local lottery machines.

The trek has been a ritual for many here, even before the eye-popping billion-dollar jackpots they've seen over the last week. And when those jackpots jump high into the stratosphere, like they did this week, so do their dreams.

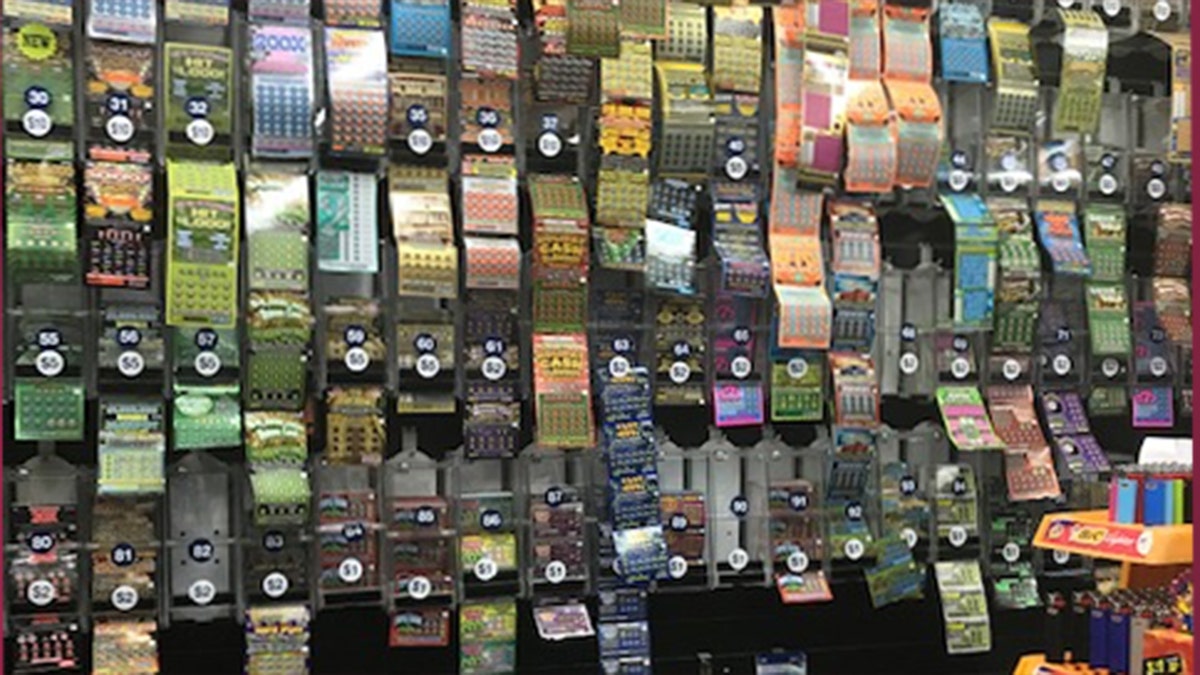

“It’s like Bingo, in a way. You have to think about your move,” said Maynor Villeda, 55, hunched over a counter at the Station Grocery, which offers an almost artful display of Powerball forms and scratch-off lottery games.

Villeda, who is Guatemalan, is a veteran player. On Wednesday night, hours before a $600 million Powerball draw, he was $10 into scratch-off games. After spending more on Powerball that night - and Mega Millions earlier in the week.

“Last December I won $1,000,” Villeda said triumphantly. “And I’ve won about $200 a couple of other times.”

He has spent thousands, he conceded. And odds are, over time, he will almost certainly lose much more than he wins. But he does win occasionally, and he says that makes it worthwhile.

Down the street, at another location, Uber driver Douglas Aguirre says he has at times spent $100 a day on lottery tickets. He has slowed that down, but there were times he was doing it several times a week.

Despite cutting back, he couldn't stay away this week - not with those huge payouts looming. “I decided to stop that, and I didn’t play in about a month. Then Mega Millions and Powerball got so high, I felt I had to buy tickets.”

The Station Grocery, a favorite spot in East Boston, offers a wall full of different lottery options. (Elizabeth Llorente)

Aguirre and Villeda represent what critics of the legal state lotteries - which have and continue to bring in billions of dollars every year - is an uncomfortable reality: Many of those who play most are the least likely to have disposable income to gamble away their modest wages.

Several studies have shown the lotteries to be what's called a "regressive tax," meaning it hits hardest those who are most unable to afford it. The odds of winning are so horrible, critics say, that it's irresponsible of states to entice lottery players to plunk down their hard-earned cash.

Unlike privately owned casinos, lotteries are run by states without competition, as monopolies. That allows them to set pricing high, and payouts low. States have also been accused of exaggerating the amount of money that goes to pay for programs like education - the ostensible benefactor of lottery funds in many places - by simply moving money around in the state budgets.

But those concerns don't seem to matter at Bella’s Market bodega, another of the many places where Aguire and other customers gather to play, talk - and share their dreams.

Maybe instead of driving a taxi, they can own a fleet someday. Or rather than clean office buildings, they’ll own one of the businesses in those skyscrapers. And goodbye to that waiter's job at the fancy restaurant. They'll be customers now, ordering their fancy. Lobster? The filet? The creme brulee?

Yes, yes, and yes. And they'll always leave a great big fat tip - because they know what it’s like to be on the other end.

East Boston is just one of the many neighborhoods around the country where working class folks live and dream, in the hopes the lottery payday takes them somewhere they fear they'll never go. The average resident here has some college, according to Bostonplans.org, but 32 percent have less than a high school degree. The most common jobs are in food preparation or serving, building, grounds maintenance, and administrative support.

Aguirre, 42, was holding Powerball tickets that, for a few hours at least, had him on a magic carpet ride.

“Birthdays, my age, my children’s ages, that’s how I pick my numbers,” he said. “I usually buy three tickets with numbers I choose, special numbers to me, that have some significance. And I get three quick-pick, I leave those up to the machine.”

Maynor Villeda, who plays lotto regularly, says some games require strategy. But the odds are generally stacked against him.

He had bought a Mega Millions ticket earlier in the week, and actually got four numbers, plus the Mega Ball. “I got $200,” he said, beaming. Then he furrowed his brow.

“But when you think about it, how huge the jackpot was, I should have gotten more than $200, don’t you think?”

And his Powerball bet? Like everyone else in the country who bought tickets for Wednesday night's draw, he lost.

But his dream endures. Aguirre said he would love to buy homes for family members back in El Salvador if he won, and donate to organizations and hospitals that serve pediatric cancer patients.

“It would be great to improve my life and be able to help people I love and strangers who are struggling, especially children - everywhere in the world.”